Immerse yourself in a fount of information about Roman water displays and discover how these features kept late antique homes cool in both style and temperature with this blog by Ginny Wheeler, author of Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West

By Ginny Wheeler | 6 min read

While the late Roman period (defined as roughly AD 250–450) has traditionally been associated with the decline of classical Rome, the many surviving remains of luxurious residences attest to a thriving upper class that continued to invest lavishly in their homes. Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West presents the first synthesis of the archaeological evidence for the prevalence of late antique water features in both urban houses and extra-urban villas across the western Empire.

Fountains and other water displays obviously served as decorative installations, but their placement and configuration lead to questions as to whether they were merely ornamental. What other motives may late antique homeowners have had to invest in them?

One reason that has traditionally been underexamined is their role in ensuring that Roman residences remained temperate, even during the peak of summer heat. Water Displays demonstrates how the strategic placement of water features in interconnected open-air, enclosed, and interior settings effectively cooled and enhanced domestic spaces, forming part of the ancient “air-conditioning” system.

Water Displays demonstrates how the strategic placement of water features […] effectively cooled and enhanced domestic spaces

Almost all the recorded examples in the book—close to 200 compiled from across the western Empire—are found within regions with hot and dry or semi-arid conditions that promote effective passive cooling through hydraulic means. Marked concentrations of villas with multiple water features in the hottest parts of Hispania reveal how integral the usage of water for evaporative cooling was for moderating the torrid climate of southern Spain.

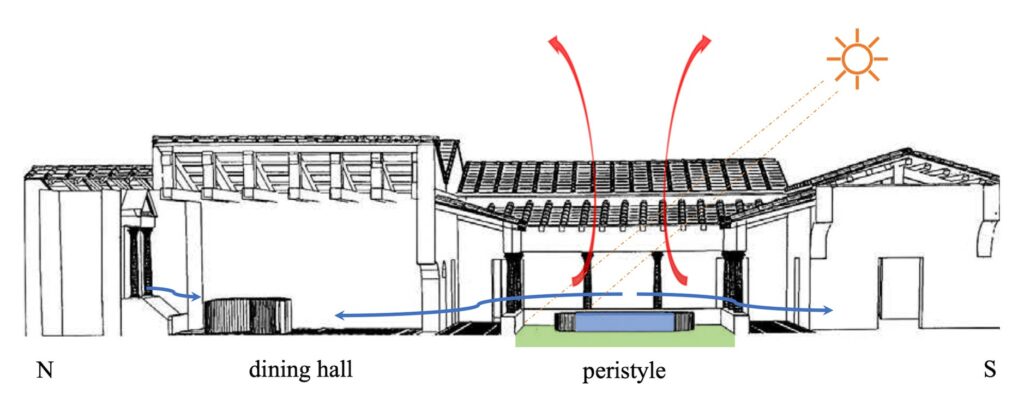

Such water-based, passive cooling strategies are well-illustrated by the late Roman villa of El Ruedo, not far from Granada in southern Spain. Originally dating to the early Imperial period, the rural villa was monumentalized in the late 3rd or early 4th century. A biapsidal pool was inserted at the center of the central peristyle courtyard, and its mosaic paving was replaced by vegetation. The main reception hall was fitted with a water-equipped, semicircular dining couch (stibadium),and a fountain was inserted just behind it, set into the space’s north wall.

The vegetation and the peristyle basin both served to lower the ambient temperature through heat absorption and evaporative cooling. The resulting differences in thermal pressure would then have flushed the air cooled by its contact with the stillwater surface into the adjoining interior spaces. While the basin and vegetation provided passive and constant heat mitigation under hot, dry conditions, the water-equipped stibadium and the fountain behind it were active installations probably only intended for use during specific activities and times of day.

When in action, the curtain of water flowing down the sloping ramp of the fountain would have been more effective at evaporative cooling than the stillwater basin due to the dispersed water coming into more prolonged contact with the air. In addition, the descending water would have produced a refreshing mist for the diners reclining stickily close to one another, since the size and shape of the couch required them to assume a “spooning” position. The water channel around the rim of the stibadium’s circular cavity would have conveniently allowed diners to rinse their hands and cool themselves off as desired.

The elaborate staging of water was an important means by which wealthy homeowners could set themselves apart

The insertion of multiple water displays provided residents and guests with a pleasant array of microclimates from which to choose to manage their preferred levels of thermal comfort. Their assumption that such customisation in environmental manipulation was possible should not come as a surprise, given Roman builders’ well-attested understanding and prowess in moderating climatic conditions in the context of recreational baths. Centuries-long enjoyment of the established bathing sequence of rooms and pools of varying temperatures would have rendered water-based cooling an obvious strategy to deploy in residential spaces.

Late antique homeowners could have taken pride in their water displays not only for their practical and cooling benefits, but also for their aesthetic qualities, their sensorial enrichment, and their socio-cultural significance as status symbols. Almost exclusively found in connection with reception and dining spaces, water features remained an attractive form of display to generations of homeowners in part due to their creative malleability, which was key both to navigating practical constraints and to amplifying and optimizing their sensorial and thermal effects. In addition, selected decorative attributes could showcase their commissioners’ classical education and active participation in contemporary Empire-wide elite culture. The elaborate staging of water was an important means by which wealthy homeowners could set themselves apart among the competitive elite milieu in late antiquity.

Water Displays in Domestic Spaces across the Late Roman West is available from the Pen and Sword Books website at a special pre-publication price for a limited time only.

Special Price: £36.00

Featured image: Ostia Antica. Image credit: Gini George from Pixabay

Follow

Follow